Some 400,000 women get breast implants each year and 75 percent of those operations are for cosmetic reasons or augmentation. The remaining 25 percent are for post-cancer reconstruction after a mastectomy. However, a key component of that reconstructive surgery is also under fire and may be causing the same implant-associated illnesses that have thousands of women concerned and hundreds considering filing breast-implant associated illness lawsuits.

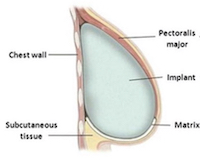

Earlier this year, the FDA began reinvestigating the data around the mesh used to support reconstructive implants in women who have undergone mastectomies. The mesh; a small patch of bioengineered tissue about the size of a cell phone, is used to help cradle and support the implant once it is put in place. At $3,700 a piece, it is a vital – and expensive – aspect of the reconstructive process.

About 72,000 women have the mesh used in their breast reconstruction each year. And, data shows that there is a strong chance that it is responsible for a number of post-operative complications including infection, swelling, and overall failures in the reconstructive effort. In most cases, those failures lead to the removal of the implant.

The number of complications associated with the mesh, however, are set to skyrocket as mesh manufacturers are looking to expand their use into non-reconstructive applications like cosmetic procedures. And it’s starting to look like the federal agency tasked with regulating the safety of the drugs and medical devices Americans use every day may be powerless to stop it.

“For better or worse, the [mesh] products are already on the market, so manufacturers may not be highly motivated to do testing. It’s almost like the cat is out of the bag. It may be too late to try to get clinical trials.” These are not the words one expects to hear from a member of the FDA panel tasked with determining the safety of these reconstructive meshes. When it comes to regulation and taking action on things that may do us harm, the words “it may be too late” to act should never have to enter the conversation.

Still, while women continue to try to draw attention to the fact that they are suffering real, tangible injuries as a result of the implants and meshes used in so many procedures over the decades, the FDA continues to reiterate its sad – and quite neutered – commitment to conducting more studies.